Christian Nationalism and Declining Denominationalism

The resurgence of Christian Nationalism today mirrors 19th century America's generic Protestant consensus. How does declining denominationalism connect to Christian Nationalism?

Over the past few weeks, I have been teaching Sunday School at a local Presbyterian Church in Macon, Georgia. I decided to focus on Christian Nationalism, examining the term itself, discussing how Biblical and Constitutional traditions understand the relationship between religion and civil governance, and finally exploring Christian Nationalism in global context.

As I've written previously, I struggle with the term "Christian Nationalism" because its varied definitions diminish its precision. Sociologists studying contemporary Christian Nationalism often understand the term in ways that would be historically anachronistic, though not all scholars agree on its parameters.

Some clergy have recently suggested that Christian Nationalism dates back to Roman Emperors Constantine and Theodosius, who endorsed Christianity as the Roman Empire's preferential religion. While I understand this sentiment, applying such a modern term to the fourth century represents anachronistic and imprecise historical analysis. Examining Christian Nationalism historically requires careful consideration, recognizing it as a ‘second order,’ scholarly construct rather than terminology historical actors would use. More accurately, Christian Nationalism must be understood in relationship to modern concepts of nationhood and the rise of the nation-state.

After spending a class period discussing the multifaceted use of "Christian Nationalism" in popular discourse, we devoted the next week to studying Biblical and Constitutional traditions regarding religion and civil governance. Toward the end of our conversation, one gentleman asked an insightful question: given my expertise as a historian of American religion, what similar characteristics exist between contemporary Christian Nationalism and forms we might identify in earlier periods of American history?

His question reminded me of research I conducted for my forthcoming book Minister Factory: The Politics of Theological Higher Education in Early America (UNC Press, 2026). After reflection, I responded that when comparing contemporary American religious life with the early nineteenth century, I see a striking parallel—weak denominational structures alongside a generic Protestant consensus.

Nineteenth Century Nonspecific Protestantism

When we think of the early nineteenth century in American religious history, we do not often think of weak denominationalism, but rather the rise of denominationalism. Americanist Tracy Fessenden’s work Culture and Redemption: Religion, the Secular, and American Literature, however, suggests that during the early nineteenth century there emerged a type of nonspecific or secular Protestantism. In essence, Protestantism became the de facto mode of American culture and governance.

During this period of American history, it was not that the government or country sought to espouse any particular type of religion, but rather Protestantism was simply permeated society. When public schools practiced Bible readings, for instance, the King James Version was the generic, Protestant default rather than the Roman Catholic Duey-Rheims translation.

While yes, denominational groups did disagree over particular theological tenets, overall, there was quite a bit of shared commonality. Theological seminaries are a great example of this in the early nineteenth century. While seminaries and divinity schools were founded by particular denominational traditions, they remained open to accepting students from across denominational backgrounds. Neither numerical strength nor financial resources allowed these schools to operate in isolation of other denominational traditions.

The Plan of Union between Congregationalists and Presbyterians further illustrates this nonspecific Protestant sentiment. As the country expanded westward, neither Congregationalists nor Presbyterians were stronger enough to settle the frontier on their own. The Plan of Union became a mechanism of nonspecific Protestant cooperation dedicated to filling pastorates to Christianize the frontier.

This generic or nonspecific Protestantism fueled xenophobia against Irish Catholic immigrants and justified policies of Indian removal. It shaped cultural reform movements like the Temperance movement and American Tract Society that sought to prohibit alcohol and inundate the country with generic Protestant literature respectively.

This generic Protestant consensus fueled a religious nationalist fervor. However, as denominations grew and became stronger toward the middle of the nineteenth century, however, policies like the Plan of Union and this generic Protestant consensus weakened.

The Decline of Denominationalism Today

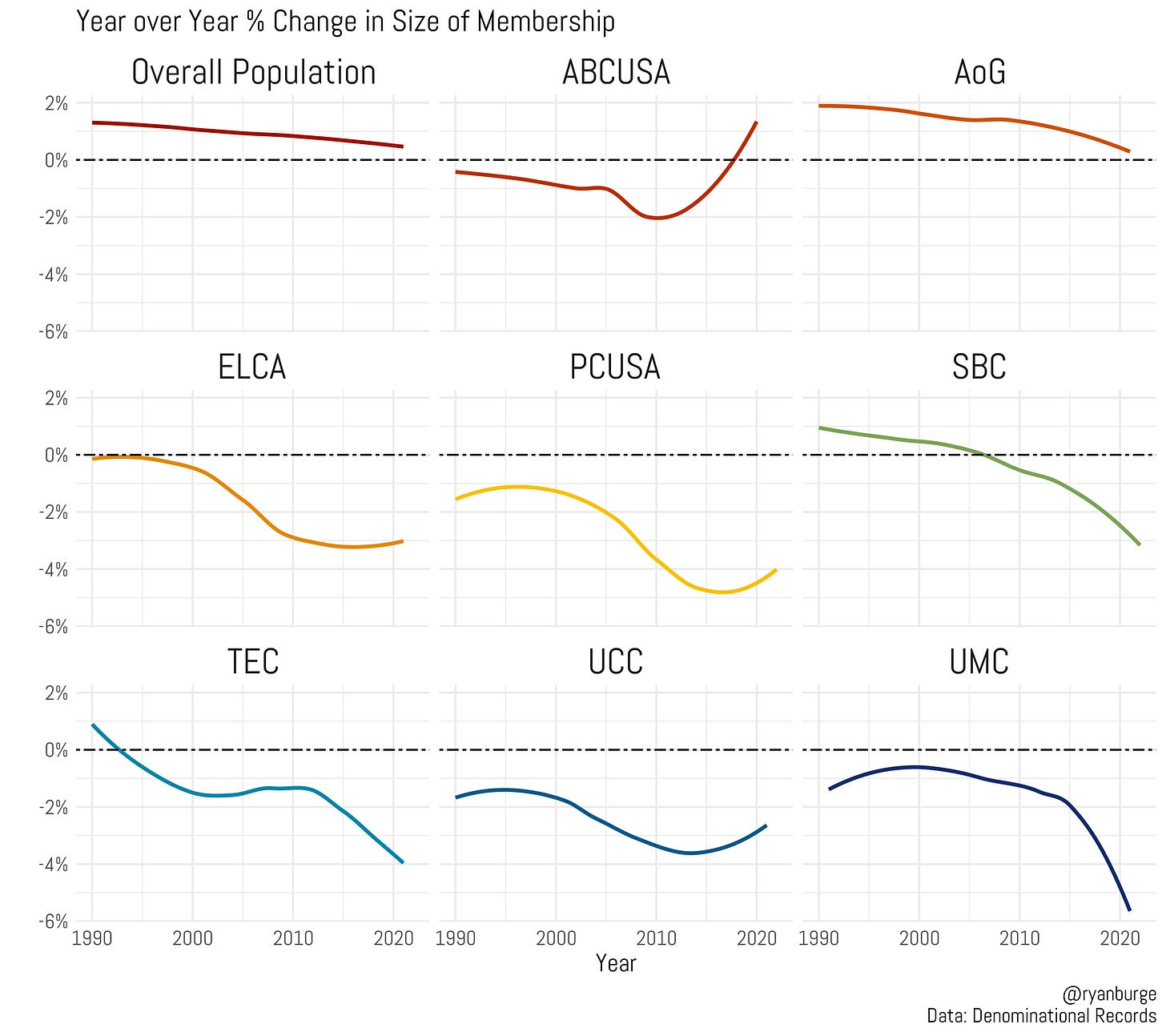

Beginning in the 1970s and 80s, sociologists began to notice that denominational strength was beginning to decline—a trend that has only accelerated. Today, most mainline denominational bodies are at their weakest point in over a century. Denominational agencies, seminaries, and paradenominational bodies are struggling financially and having to adapt to a “post-denominational world.” Meanwhile Christian Nationalism appears to be doing quite well.

I think denominational particularity offers important resources for confronting Christian Nationalism. The term, itself, presents a generic Christianity. I have seen no talk of Lutheran Nationalism, Baptist Nationalism, or Methodist Nationalism. Christian Nationalism relies upon an opaque, generic understanding of Christianity. It is not rooted within any particular tradition.

This is not to suggest that denominationalism is inherently good and that nondenominational churches are inherently bad, rather it suggests that a rootedness and specificity provide productive frameworks for countering an ideology like Christian Nationalism.

As I explained to the Sunday School class, when their Presbyterian Church made a decision, they were accountable not only to the wider PCUSA denominational body but also to the tradition of Presbyterianism. Their decisions must reckon with their rootedness in this tradition. Nondenominational churches, as well as autonomous Baptist churches, have little denominational accountability but must still work to ensure their rootedness within a free-church tradition.

Denominationalism is unlikely to stem the tide of its decline to rise to combat the generic and nonspecific Protestantism that animates much of contemporary Christian Nationalism. Understanding Christian Nationalism's surface-level religious framework—and recognizing the importance of rootedness and tradition in response—offers one tool for countering this problematic movement in American religious life.

Please like, comment and share as you are inclined. If there is a topic that you would like me to write about or if you would like to collaborate, contact me at abgardner2@gmail.com