Church Oligarchy!!

How does our current oligarchic politic climate resemble the climate of church politics?

Oligarchy seems to be the new buzzword in American society and for good reason. It describes our current political and economic situation quite well. Given the state of our two-party system, many of our elected officials are beholden to a small group of ultra-wealthy benefactors who leverage their financial status to dictate the direction of legislation or even now serve in the Presidential administration.

In many ways, we are living through a second Gilded Age. The first, characterized by the rise of Robber Barrons and immense wealth inequality, lasted from the mid to late nineteenth century into the early twentieth century. Instead of Carnegie, Rockefeller, and Morgan, we now have Zuckerberg, Musk, and Bezos, among others.

Oligarchy is not only a helpful term for describing the current state of American political life but also a helpful term for thinking about church political dynamics. Over the past decade, I have attended Presbyterian, Episcopal, and Baptist congregations, all of which have had oligarchical tendencies.

In most churches there always tend to be individuals or families who seemingly have an outsized say in congregational decision-making processes. These may be legacy families who have been part of the congregation for generations. Depending on how long a particular family may have attended a congregation, they believe they have an important voice in congregational decision-making.

Other individuals may be wealthy and give a significant portion of the congregation’s budget. As congregational attendance declines and budgets shrink, wealthy members become even more consequential within congregational politics. As much as we may preach that church is not about budgets and buildings or attendance and giving, churches also employ individuals who rely upon congregational giving.

Declining attendance and giving stress church employees as well as lay leaders (employers), albeit it in much different ways. Given these dynamics, it is important to consider how and why church oligarchy exists.

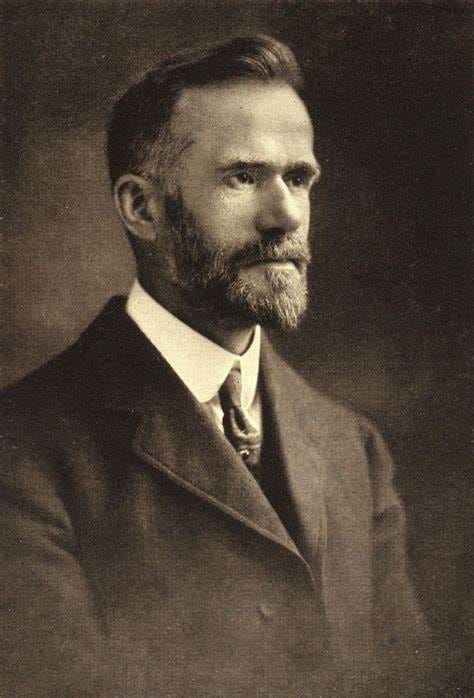

Walter Rauschenbusch and Church Oligarchy

As we brave this second Gilded Age, there is much to be gleaned from the wisdom from the previous Gilded Age. I regularly think of Walter Rauschenbusch during this historical era—the Baptist minister from New York who wrote extensively on the rise of the Social Gospel. For Rauschenbusch, the Social Gospel was deeply rooted in democratic ideals and sought to counterbalance the individualistic and revivalistic tendencies of Christianity in the late nineteenth century.

In one of his most well-known works, Christianity and the Social Crisis (1907), Rauschenbusch addresses the consequences of economic inequality on congregational politics and decision-making. As a Baptist, he was most familiar with a congregational polity that follows a more democratic form of decision-making. He contended,

…the Church has the greatest possible interest in a just and even distribution of wealth. The best community for church support at present is a comfortable middle-class neighborhood. A Social system which would make moderate wealth approximately universal would be the best soil for robust churches. (291)

Rauschenbusch’s observations feel quite timely given that educated, middle-class families today are far more likely to be regular church attenders than lower- or upper-class individuals and families.

He continues,

If a church is composed of many wage-workers with a few well-to-do families, the contributions of these few will be of inordinate importance in the financial affairs of the church. The departure of a single family may mean that the church can no longer pay the minister’s salary nor support itself. (294)

Again, Rauschenbusch’s observations are quite relevant for the current moment. Declining attendance and giving put pressure on church budgets and make ‘well-to-do families’ all the more consequential for churches to end the year in the proverbial black.

Wealth inequality coupled with declining attendance and giving can lead to unhealthy oligarchical tendencies, as churches and leaders may defer to wealthy individuals or legacy families in decision-making processes. These circumstances may push a congregation in this direction.

There are pull factors too. Families who have attended a church for generations or individuals who give significant portions of the budget feel they have more of a stake in their church’s direction or even survival. Presumably, they see the congregation’s past successes as part of their own contribution to the life of the congregation.

Rauschenbusch notes this as well: “It would be strange …if those who are financial stays of the church did not have the feeling that their wishes ought to be decisive about the coming and going of the minister and other matters deeply affecting the spiritual life” (295). It is entirely natural for wealthy church oligarchs to think that they should have a say in the congregation’s ministerial staff.

Both these push and pull factors contribute to the formation of what might be considered a congregational oligarchy.

Wealth Inequality and Church Oligarchy Today

According to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, the top 10% of households hold 67% of the country’s wealth. The bottom 50% hold just 2.5% of the country’s wealth. Such numbers create quite a problem for religious congregations, given Rauschenbusch’s assessment of the role wealth inequality plays in congregational politics and decision-making.

The prospect of addressing church oligarchy and wealth inequality is not simple. Lay leaders feel the stress of paying bills and covering expenses, as do ministers. Church oligarchy is not a simple matter of finances and class. Focusing on ‘class,’ while perhaps a good start, is not sufficient to understand the ways in which church oligarchy and wealth inequality inhibit congregational vitality.

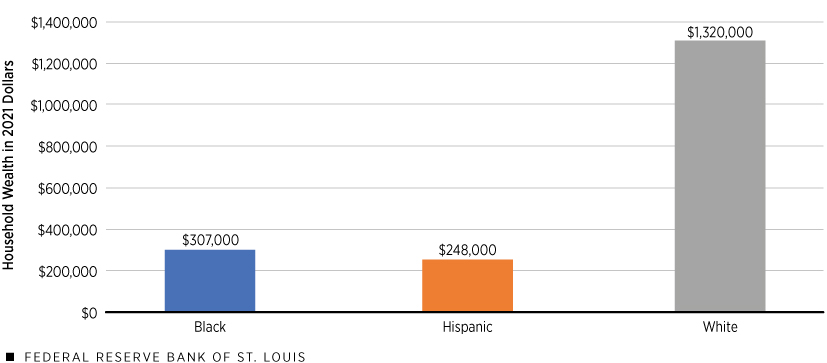

Wealth inequality is also shaped by other factors of identity beyond class that affect congregational dynamics, including race. According to the St. Louis Fed, Black families own about $.23 of wealth for every $1 of white family wealth. For Hispanic families, the number is $.19 for every $1 of white family wealth.

In addition to race, gender, and marital status also play a significant factor in determining wealth. White women hold $.56 for every $1 of white men’s wealth, whereas Black women hold just $.05 for every $1 of white men’s wealth.

Wealth is Linked to Gender, Race and Ethnicity, and Marital Status

Wealth Inequality and the presence of church oligarchs have implications for how a congregation addresses or chooses not to address issues of race and gender. As progressive churches in particular look to combat issues of sexism and racism within their congregations, it is imperative to consider the role church oligarchy and wealth inequality play within their congregations. Churches cannot effectively address any of these issues individually and must address them collectively.

Church democracy and voluntaryism presuppose approximate financial equality.

According to Rauschenbusch, “Church democracy and voluntaryism presuppose approximate financial equality” (295). Such a presupposition, coupled with the state of wealth inequality in the United States, suggests a dire state for churches committed to antiracism and gender equality. It also suggests that as gaps widen, church oligarchic tendencies will worsen.

While Rauschenbusch never used the term “church oligarchy,” I think such a term captures his descriptions of the challenges of wealth inequality in congregations. Not every church will have an oligarch class of members who hold the power to sway congregational decisions in the same way. Understanding how their power and privilege are linked not only to class but also race and gender is important for understanding how to combat and navigate church oligarchy.

Recognizing the intersections that shape the power of a ‘ruling class’ within a religious congregation is important for understanding how to pressure and push for a more equitable and more democratic congregational polity.

Please like, comment and share as you are inclined. If there is a topic that you would like me to write about or if you would like to collaborate, contact me at abgardner2@gmail.com